Ilocos, de Sur a Norte

I would wake up to the sound of waves hitting the abstract rock formation only a gaze away from the window. The breeze generously offering me comfort to defeat the summer heat. The sea always generously supplying us with a bounty of freshly caught seafood hastily carried by the local fishermen from within the neighborhood. But tucked away from this lucid image of my childhood bach memories is a town embellished by a Hispanic history I almost took for granted.

I grew up spending a lot of my summers traveling to my father’s hometown, Ilocos Sur. Aside from the reef where I would dive in most days and the flavours of the Ilocano cuisine, I realised I have been lucky to be surrounded by a beauty already acclaimed by Unesco. But as a child insouciant to what was perpetually available around me, I found myself desensitised until I grew older and gained the appreciation for the very history that forms part of my identity.

Spanning over centuries, both Ilocos Sur and Norte have preserved the ancient man-made wonders that the Philippines is left with after a 300 year Spanish era in the country. Being the only predominantly Catholic country in the East, towering cathedrals and baroque churches made from bricks and stone serve as pillars of the Filipino faith through ages, distinctively different from the golden temples and pagodas of the rest of Asia.

Ilocos is home to many of these colonially influenced architectures. Tested both by time and the unforgiving forces of nature. they remain strong and standing, a reflection of Filipino resilience.

The Church of Our Lady of Assumption, or better known as Sta. Maria Church in Sta. Maria, Ilocos Sur is built out of bricks and mortar. It was purposely hoisted on top of a hill to act not just as church but as a citadel of the Spaniards where attending a mass requires eighty five stairway steps to the top.

Saint John of Sahagun Church in Candon, Ilocos Sur unique marvel is painted on its ceiling. The earthquake baroque-designed church is the house of the longest religious painting in the Philippines with 150-feet visuals of the 20 Mysteries of the Holy Rosary.

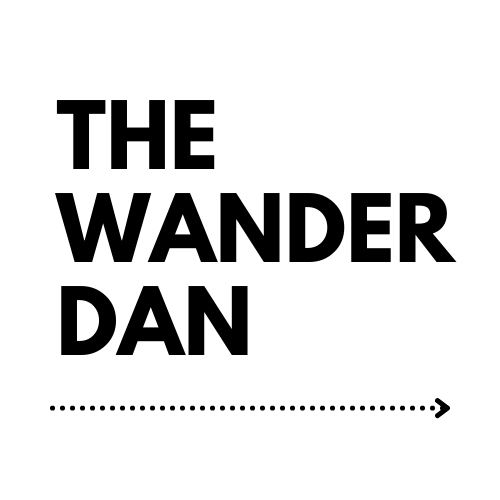

Nesting at the epicenter of Ilocos Sur’s capital, Vigan is the Metropolitan Cathedral of the Conversion of St. Paul the Apostle It is designed with Neo-Gothic, Romanesque and Chinese inspired adornments. The rooster that sits on top of the bell tower symbolizes St. Peter.

While meddling in the capital’s busy pace, a short walk from the cathedral led me to the most famous street in the northern region. Calle Crisilogo, one of the many UNESCO world heritage sites in the province. The street is a remnant of the community in a Spanish colonial era. The cobble-stoned streets today still are a passageway to many traditional carts called the Kalesa, a two-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. In the past, this used to be the mode of transportation of the affluentials, but today they mostly carry tourists to circle the heritage site.

Before entering the Calle, it has been our habit to grab a bite of the Empanada and Okoy, an Ilocano staple, which was abundant in the side streets near the plaza.

I have lost count on the number of times I have walked the aisle of Calle Crisologo but it still feels special every time perusing the exposed bricks covered by a thin layer of concrete, passing by the array of houses in what used to be the center of trade.

Driving up the northern part of Ilocos called Ilocos Norte, we are greeted by more awe inspiring architectures and more stories that made me appreciate the culture even more.

Ilocos Norte has played a great story in the political past of the country. It is the hometown of the late president Ferdinand Marcos whose regime remains a point of heated discussion even up to this day.

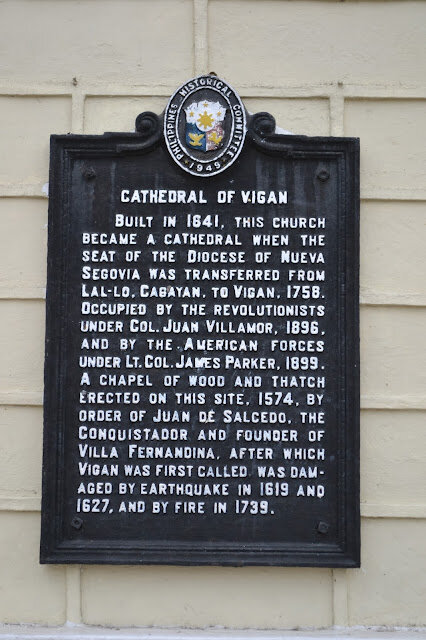

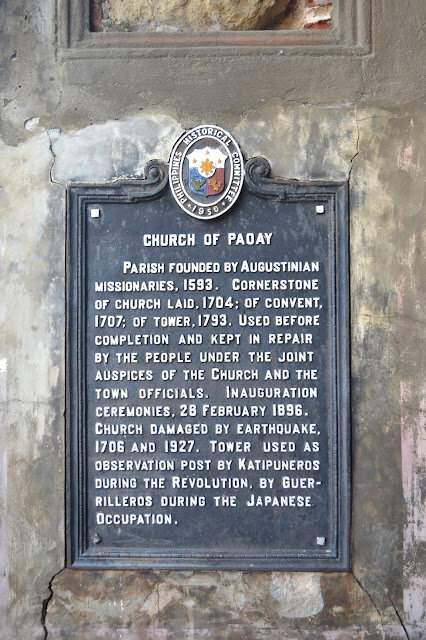

The St. Agustine Church in Paoay, Ilocos Norte is regarded as one of the National Cultural Treasures of the Philippines. The church has buttresses at the sides and the back of the stone-made church. The three-story bell tower which appears like a pagoda is upheaved at the right hand of the church's facade which altogether looks like a rising pediment.

The Malacanang of the North has a peculiar story not only because it has been mentioned frequently in school textbooks but because the location is also very uncanny.

The mansion faces the Paoay Lake believed to be enchanted. According to old tales, there was once a town where the lake is now. In this town lived a rich but selfish community. The Gods were displeased with their attitude and the ill behaviour of the men and women who lived here so the town was punished and submerged into water, the people cursed and turned into fishes. Fishermen who came to catch fish from the lake said the fishes they caught wore earrings on either side of its gills, they believe these fishes were the rich people cursed to live in the waters.

The mansion right next to the lake boasted classical sophistication. Many of the banquettes and meetings hosted by the past president were celebrated in this residence. The mansion went through a long journey of legal discussion as the government believe that the mansion was built out of public funds so this was sequestered from the Marcos'. Eventually, the mansion was returned to the family and has since become a tourist attraction.

We continued our journey to the Norte’s capital, Laoag and marveled at the novelty of the Sinking Bell Tower, the country’s tallest bell tower, which for some bizarre reason was standing eighty-five meters away from its adjacent church, the St. Williams Cathedral. Because of the tower’s sandy material, it has started to sink that I had to bend to enter.

Before driving back to the Sur, we took a moment to meander at the Marcos Museum. Preserved literature, artifacts, clothes, jewelry and artworks were amusing to see but what was more interesting was the wax-preserved body of the late president, resting inside a lighted glass box in a dark and cold room where photography was not permitted. Although I had reservations in believing, they said this was the real body of the president who died in exile in Hawaii in 1989. While there is the contention of whether or not he should be buried in the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Heroes Cemetery), the body is preserved by delicately covering it with wax and retouched every ten years. Or so they say.

Although I have spent so many years back and forth in this town, it was only then that I truly realised the importance of connecting to a town more than just as a visitor. A hometown I can share with my father’s warm townsmen, decorated with so much architectural beauty and graced by the wealth of the ocean, the wonders of its natural resources and landmarks. It gives me so much understanding and appreciation of the heritage I share with many other, the bicultural melange running through our veins and a talented, courageous and noble ancestry I can be proud of.